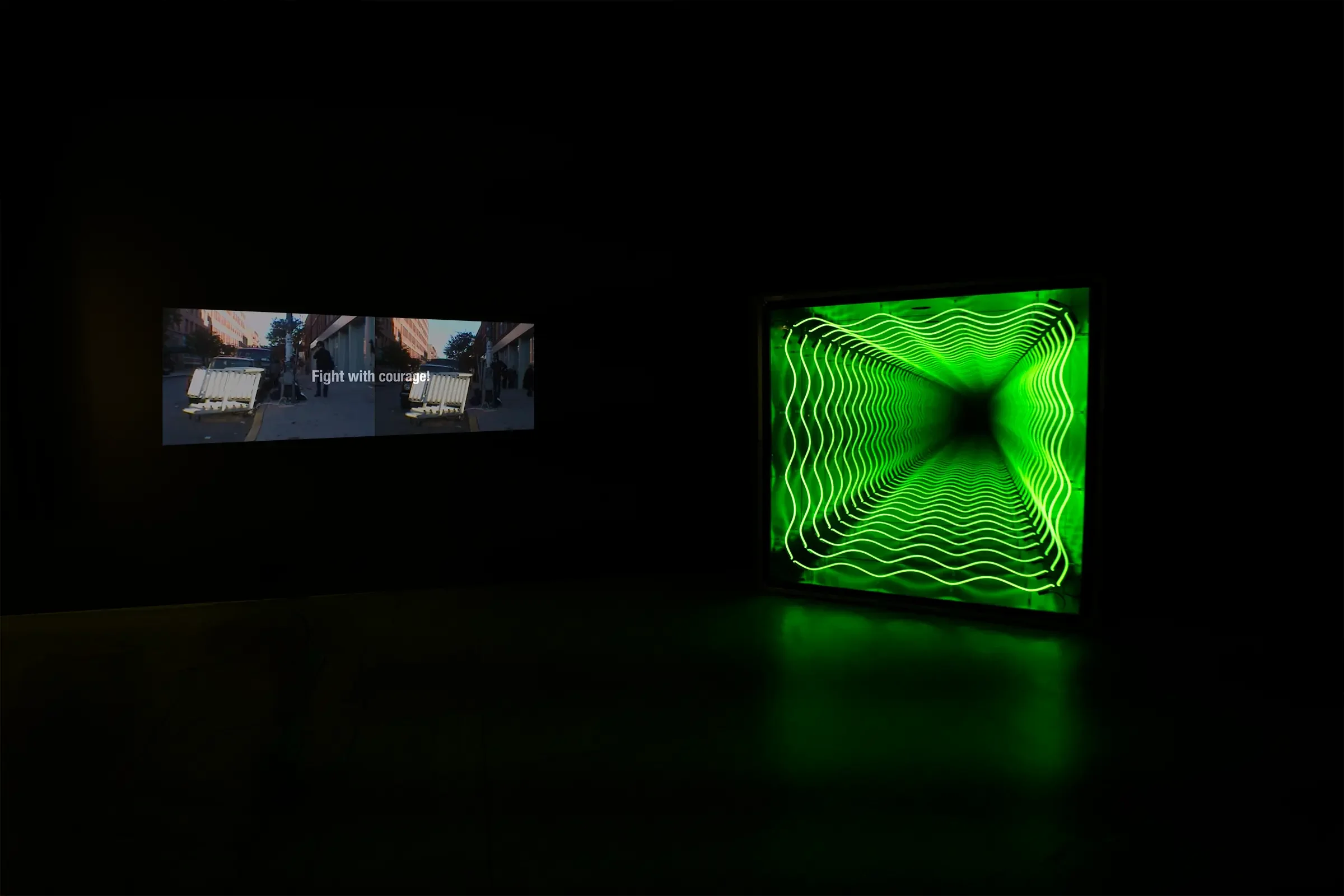

Left: Impenetrable Room, 2016 | Middle: Iván Navarro | Right: The Void, 2013

From 19 October 2025, GMAC will present a solo exhibition devoted to the work of Iván Navarro. Drawn from signature works in the collection assembled by George Merck, Charged: Iván Navarro and the Aesthetics of Power, brings together three works made between 2013 to 2023, including two large-scale neon works and one video piece. The show is accompanied by a publication featuring a commissioned essay by Dan Cameron and text by the show’s curator Anna Valverde.

At its core, the exhibition invites viewers to consider the dual nature of light in Navarro’s pratice—its seduction and subtext. While light-based art often elicits a phenomenological response rooted in perception and formalism, Navarro’s engagement with light is also distinctly political. His work transforms the aesthetic language of light into a vehicle for historical consciousness and collective memory.

Curator's text:

Light as Witness by Anna Valverde

To understand the symbolic resonance of Navarro’s use of light, we must understand Chilean history during Augusto Pinochet’s rule. During Pinochet's dictatorship, under which the artist grew up, it was common for those with dissenting views to be "disappeared" off the streets and subsequently tortured. This well documented torture took many forms, including sensory deprivation and assault. More vividly this translated to denying prisoners sleep by playing loud music and shining bright lights. Pinochet’s power was also enforced through controlled blackouts as the strategic cutting of electricity became a mechanism of fear and subjugation.

Against this backdrop, Navarro’s luminous structures operate on multiple registers—formal, symbolic, and metaphoric. Light becomes both medium and message: a conduit for beauty and revelation, and simultaneously a reminder of surveillance, authority, and confinement. His works—often framed within minimalist geometries such as doors, ladders, or road cases—evoke the aesthetic restraint of Minimalism while embedding within it a moral and historical charge. Like Janus, Navarro’s light faces two directions: one of transcendence, the other of control.

To address themes of violence and oppression through visual art requires a particular equilibrium of sensitivity and intellect. Navarro achieves this with uncommon grace. His works do not accuse; they illuminate. They offer viewers a space of reflection—where empathy, inquiry, and awareness can coexist. That even those who benefit from the systems of power his art interrogates can stand before it and engage is a profound achievement.

It is a privilege to have worked on this exhibition—to learn from Navarro’s practice and to witness how light, in his hands, becomes both an aesthetic and ethical force.